Friends, I feel that Studio Notes needs a structure, so I’m going to try something new, starting with housekeeping items and announcements, such as this one.

After some thought, I’ve decided to make this a monthly newsletter, in synch with the full moon. This way, I can better focus on my art practice as well as on other writings that are beginning to clutter my mindspace.

In this Studio Notes, though, I’m excited to tell you about my artist crush, Ithell Colquhoun. And what is a crush but being infatuated by projected parts of the self onto an idealized other?

Get cozy, because it turns out I have a lot to share. But before we begin,

Announcement: Private lessons now available!

I’m excited to offer private lessons in oil painting and drawing, customized to your personal goals and experience, both in-person and online. I truly believe that one-on-one sessions unlock a depth of learning that's hard to match. You can book a single afternoon deep-dive or a series of private sessions.

Lessons are $60/hour. Paid Substack subscribers receive an additional 15% discount.

Please, inquire if interested. I’d love to paint with you ♥.

On Ithell Colquhoun

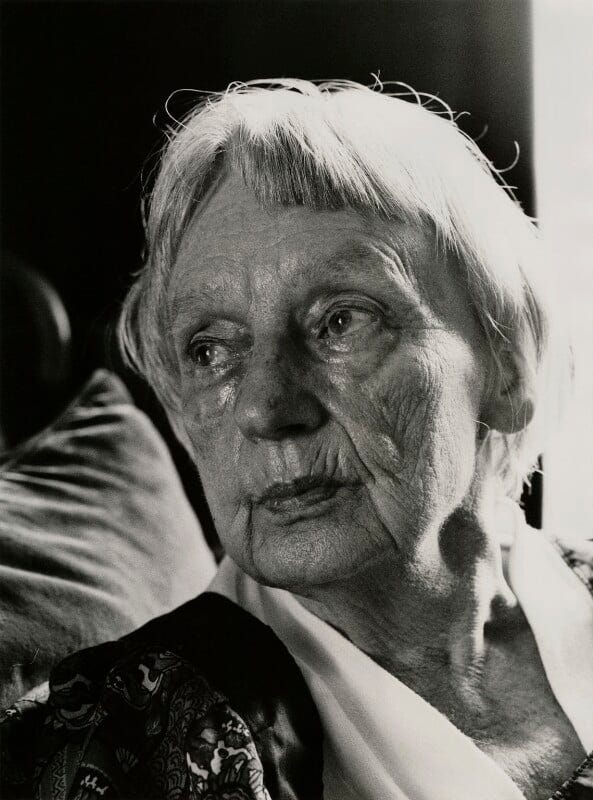

I recently finished Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of the Fern Loved Gully (2020), by Amy Hale, a biography of the brilliant yet largely forgotten artist and writer Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988). Thankfully, she is experiencing a significant posthumous comeback. In 2019, her extensive archive was acquired by the Tate, which hosted the first retrospective exhibition of over 200 paintings earlier this year (February to May 2025).

I wrote about my burgeoning love of Colquhoun in a previous Studio Notes. While she left behind an equally impressive collection of writings, including published and unpublished novels, nonfiction books, articles, poetry, and essays, here, I will focus on Colquhoun’s unique artistic practice.

Art as Extra-dimensional Portal

Colquhoun is often grouped with the Surrealists, and she was, indeed, a prominent figure in British Surrealism in the 1930s and 1940s, but her art is so much more than that. Her artistic practice was inseparable from her search, fully in service to it, and she embraced various forms of automatic techniques as vehicles to communicate with and give form to transcendent dimensions—not so much as a means of probing the subconscious mind, as was more common within the Surrealist movement. As Hale writes:

“The artistic expression of an extra-dimensional portal represented an important spiritual concept for Colquhoun, namely that we are surrounded by other worlds and Otherworlds, and that with the right spiritual technology we can contact them. She believed that people in other times had the ability to move between worlds, and she was not only interested in apprehending those dimensions herself, but longed to represent their mysteries to others [emphasis added]”.

The question of enlightenment through art mattered most to Colquhoun, and her vast body of work is a deep pool of occult experimentation, rich with hermetic references and magical correspondences. She was influenced by several thinkers, including Russian philosopher P.D. Ouspensky, whose work on the fourth dimension had become popular with many artists, including pioneers of the Cubism movement who dared to reimagine perspective. Colquhoun saw her art practice as a means of developing fourth-dimensional vision.

Colour as Entities

Colour is central to Colquhoun’s artistic and magical practice, and without an understanding of the Golden Dawn system of Kabbalistic colour attributions, one cannot fully understand the full meaning and intention behind her work.

Hale provides some historical context I find fascinating, for it shows how technology often intersects with the magical imagination, shaping culture in unforeseen ways. When the Golden Dawn was founded in 1888, a new era of colour experimentation was underway, made possible by the development of a wide range of artificial pigments, including new colours released by the still-operating Winsor & Newton paint company. Such innovation was undoubtedly transformative for many artists at the time, unlocking bold hues that blending alone could never achieve. For Golden Dawn magicians and artists Moina Mathers and Florence Farr, these new pigments enabled the formulation of the theoretical framework for colour experimentation that would become emblematic of the magical organization’s ritual practice. Hale explains:

“What developed as a result is an exciting set of ritual practices and meditations which combine traditional esoteric colour correspondences, and the idea that colours were themselves entities which could be invoked, with newly emerging ideas about the effect of colour on physiology and the psyche.”

A lifelong student of the Golden Dawn system, Colquhoun saw colours not as symbolic representations of archetypal principles, but as gateways to experiencing colours as forces in themselves.

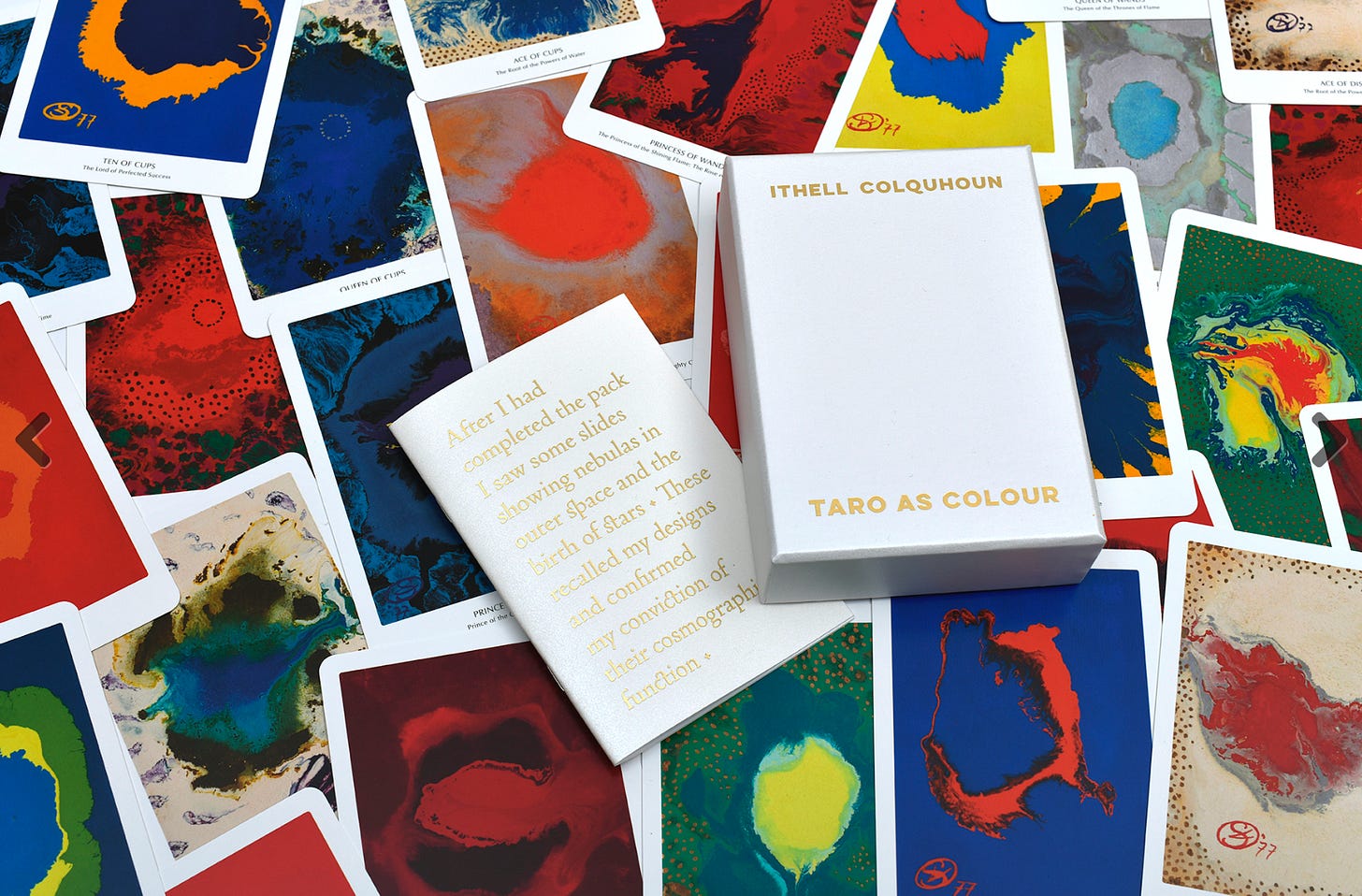

Her magical and artistic practice is exalted in her gorgeous Taro as Colour (1977), one of the first abstract tarot decks ever created and one of the early decks informed solely by Kabbalistic colour correspondences. Created with bright, opaque enamel paint, each of the 78 cards is stripped of enigmatic symbols, sigils, and narrative elements, offering the viewer direct access to the card’s underlying essence or even plane of reality. Colquhoun designed this deck specifically for meditation and contemplation, as a means to refine one’s ability to journey to worlds beyond.

Alchemical Erotica

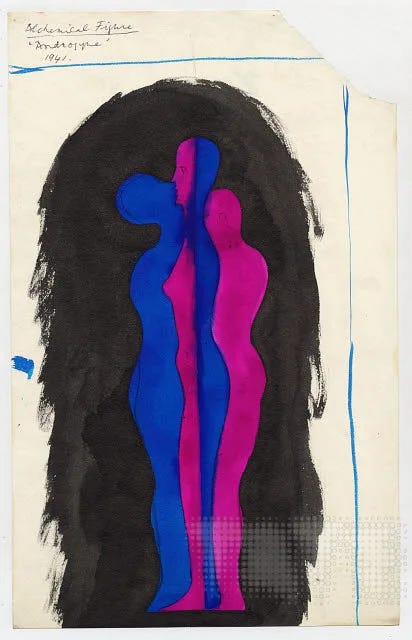

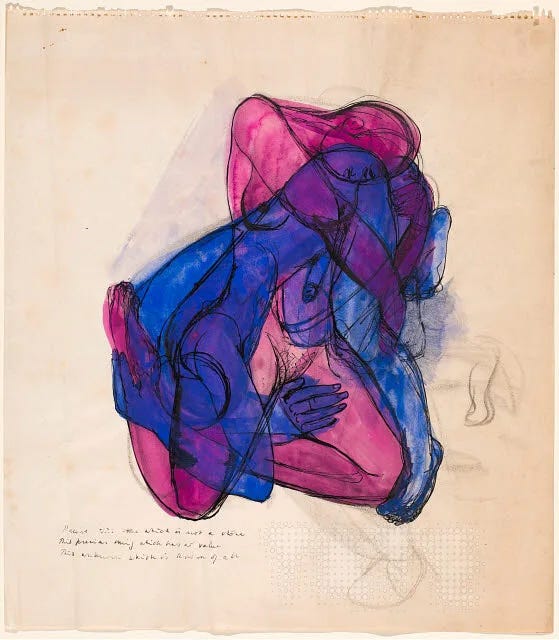

Beyond colour, Colquhoun’s work mainly explores themes of sex, magic, death, and decay—all themes I resonate with. She was especially fascinated with the image of the divine hermaphrodite, which she imagined as a perfected state of being in which the primeval polarities, male/female, are in conjunctio, and as such, transcended. Her vision of sacred alchemical union went beyond conventional ideas of gender, and throughout her life, Colquhoun had romantic relationships with both men and women.

In private, Hale reveals that “Colquhoun explored the world of alchemical erotica like a woman obsessed.” Through Kabbalistic, Tantric, and alchemical symbolism, she formulated her own philosophy and practice of sex magic, which was, of course, radical for a woman of her time.

In Sex Magic: Ithell Colquhoun’s Diagrams of Love (2024), Hale unveils a striking selection of Colquhoun’s erotic paintings, drawings, and poems. This beautiful little art book, published by the Tate, brings her voice and imagery into renewed conversation with the occult subcultures that shaped the early 20th century, while also offering a rare woman’s perspective and take on the sex magic theories that were circulating in underground British magical communities—of which Colquhoun was very much an insider.

Among the Living Stones

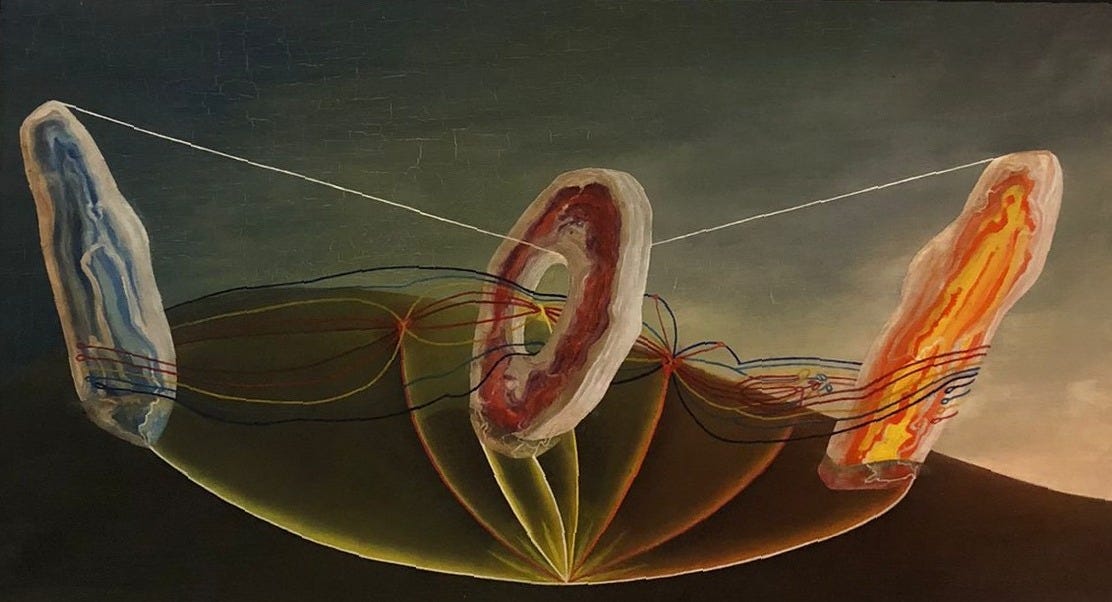

During World War II, Colquhoun left chaotic London and settled by the sea in witchy Cornwall, where she felt a deep connection to the land and to the enigmatic megalithic stone circles that had stood there for millennia. She was passionate about ancient sacred monuments, which she viewed as remnants of a lost pre-Celtic civilization—an idealized people, magical and technologically advanced, who lived in harmony with the land and knew how to harness its powers.

Based on Colquhoun’s writings—for instance, she wrote an uncommon travelogue about Cornwall, The Living Stones (1957), featuring odd cultural and historical facts as well as sacred landscape illustrations that some could read as overtly erotic—and her megalith paintings, one could say that she was a pioneer of alternative archaeology. As early as the 1940s, she was exploring ideas about electromagnetic currents (today known as telluric currents) and ley lines, considering whether these ancient sites functioned as portals to other dimensions. Hale notes that it was not until the 1960s that these ideas coalesced into the Earth Mystery movement. Still, they were not uncommon in the Atlantean lore of Western esotericism that Colquhoun was steeped in.

Touched by the Hand of Ithell

Colquhoun’s ideas were indeed “out there,” even too out there for the British Surrealist Group, and she was expelled from the organization in 1940. Her magical painting practice was shaped by a Venn diagram of obscure interests that fueled her spiritual search. Sadly, despite her brilliance, she never managed to articulate her theoretical framework in a way that was easily accessible. Her writings are often impenetrable, even to those with a foundation in esoteric concepts. Besides, women artists were largely dismissed in her day. When she died in 1988, at the age of 82, Colquhoun left, in Hale’s words, “an odd sense of defeat behind her.”

Regardless, Colquhoun was a woman well ahead of her time— weird, outspoken, well-read, and unapologetic, and that’s what I like about her. I see in her example a call to claim my identity as an occult and esoteric artist, and I guess, writer (I’ve even reworked my about page). Interestingly, some artists have identified a strange phenomenon, as if, when encountering Colquhoun’s work, her spirit begins shaping their life and practice in unforeseen ways. I think that I, too, have been touched by the “Hand of Ithell”.

Final Words

What I’m Working on: It’s been hard to spend any time in my studio, and I haven’t been super productive. Summer is always like that; summer is for adventuring! I’ve been out of town, or out and about with friends, enjoying the sunshine. Still, my hermit part finds it somewhat exhausting and quietly dreams for long, uninterrupted periods of focused work in the studio (Fall will come again).

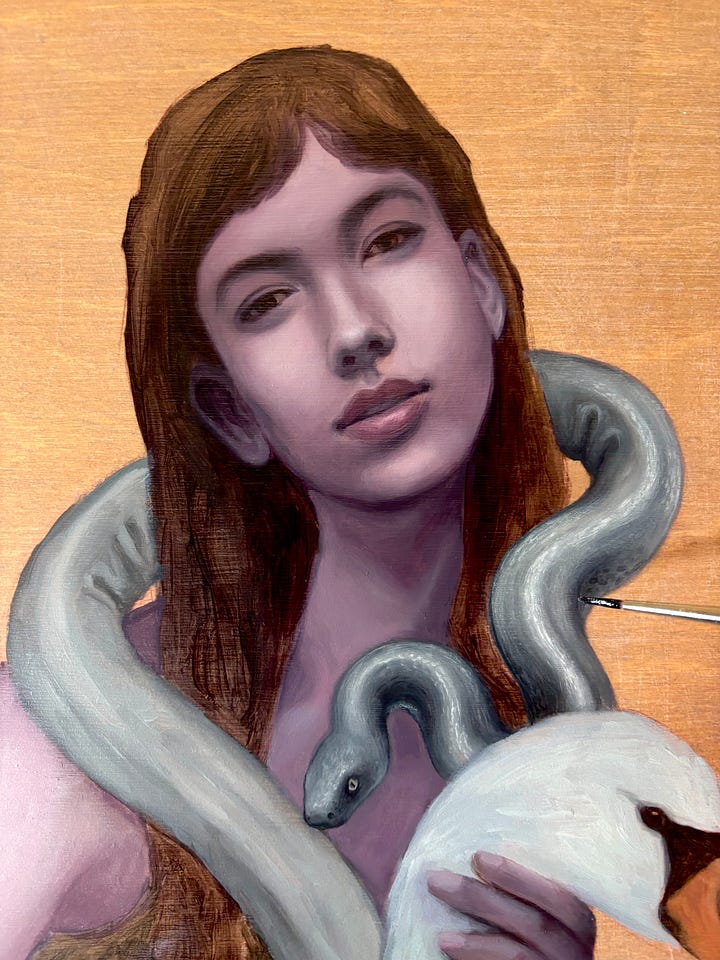

Still, I was able to complete the second layer of this painting, which I might title Sing Me a Swan Song. I’m hoping to finish it before I head off to Iceland in a week. Fingers crossed…

What I’m Reading: The book I’ve always wanted to read but didn’t know existed until I found Erik Davis’s TechGnosis (1998), where media studies meet occult history.

What I’m Listening to: I guess I’m in my Erik Davis era, my new fave media theorist. Check out his Expanding Mind podcast, where he explores the culture of consciousness, discussing topics at the intersection of magic, psychedelics, and technology.

Thanks for reading. It was a long one! I hope you found something of value that kindled your creative flame. Let me know in the comments. ♥

Thank you for sharing. She sounds fascinating! I’ve experimented with colour in poetry, influenced by Goethe’s theories. My poem ‘A Midsummer Nightmare’ attempts to evoke the primal colours black, red and white. PS. I’d recommend Of Monsters and Men’s first album ‘My Head is an Animal’ as a soundtrack for your Iceland trip – Enjoy!

Thank you for sharing, I enjoyed learning about her! Curious about that tarot deck.